Authored by Reda Ait Alla

Illustrated by Parham Ghalamdar

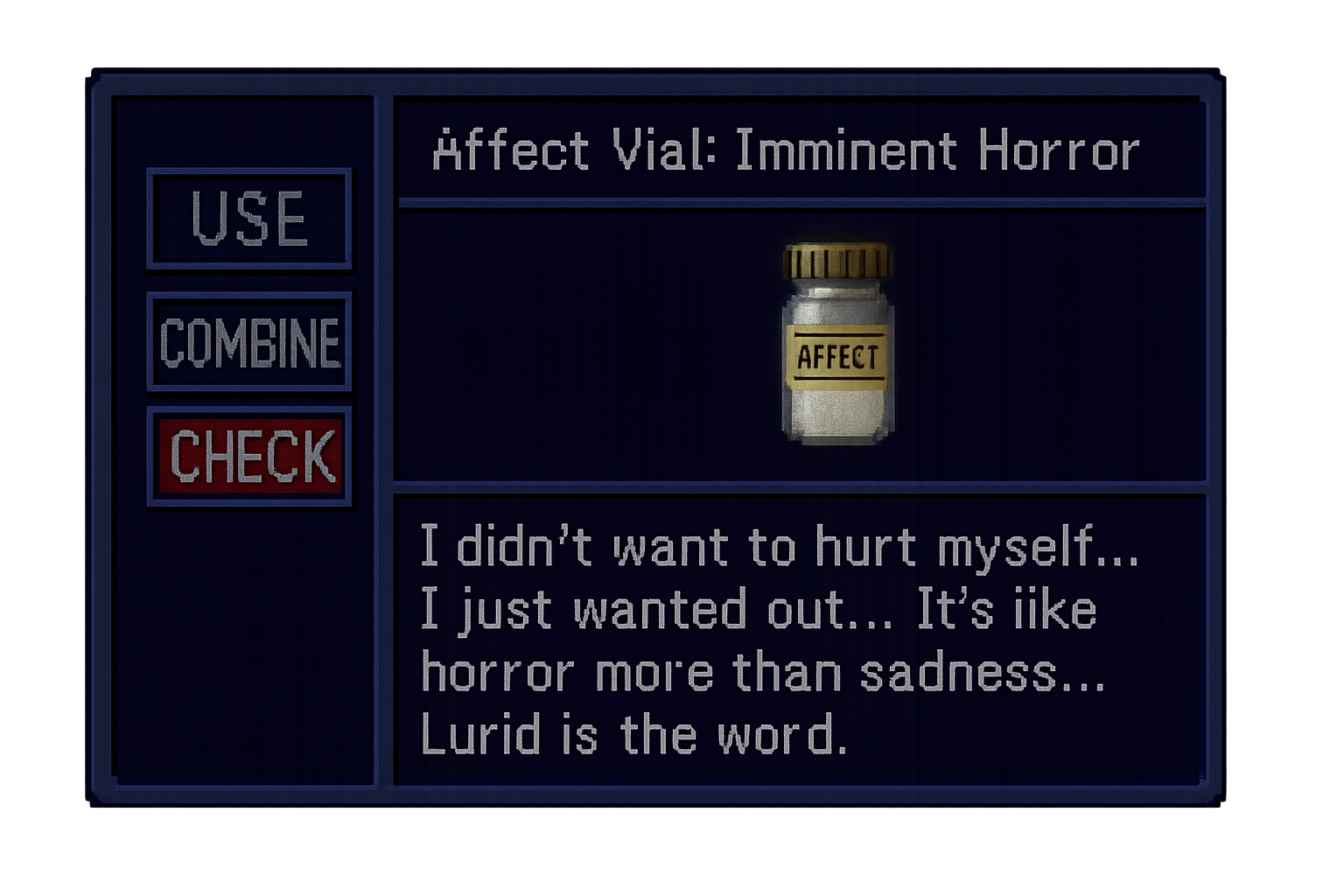

“I didn’t want to especially hurt myself. Or like punish. I don’t hate myself. I just wanted out. I didn’t want to play anymore is all. […] Well this isn’t a state. This is a feeling. […] It’s like horror more than sadness. It’s more like horror. It’s like something horrible is about to happen, the most horrible thing you can imagine – no, worse than you can imagine because there’s the feeling that there’s something you have to do right away to stop it but you don’t know what it is you have to do, and then it’s happening, too, the whole horrible time, it’s about to happen and also it’s happening, all at the same time. […] Lurid is the word.“

David Foster Wallace – Infinite Jest

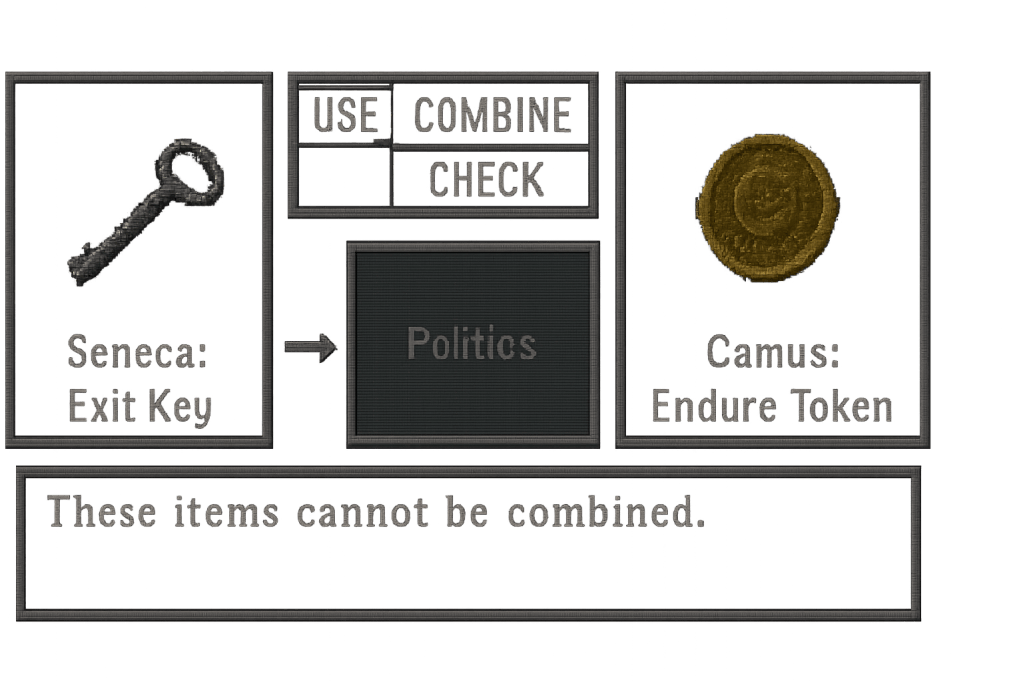

Suicide is commonly interpreted as an individual act of renunciation of life, a melancholic path stoically leading to death. Seneca extols the feats of the suicidal who has turned into a rebel against the rational order of the cosmos by vehemently choosing the easiest way: “I have made nothing easier for you than to die. […] Do you not blush to spend so long a time in dreading what takes so short a time to do?” Albert Camus, on the other hand, views it as a reverse renunciation of an absurd freedom that drives the individual, like Sisyphus, the “proletarian of the gods,” with a passion for life that refuses the invitation to death. Thus, whether through revolt or renunciation, suicide, through these two lenses, appears only as the abrupt expression of a total and infinite individual act resulting from an existential acceptance of the ultimate experience of Yama. Yet, such an interpretation of suicide – making it the only “truly serious philosophical problem” – simplifies the question by diverting it towards that of metaphysical freedom. A question at the crossroads of ethics and psychoanalysis that confines suicide to individual factors alone, hence the need to apprehend it as a political category in a collapsed system.

An Unnamed Epidemic

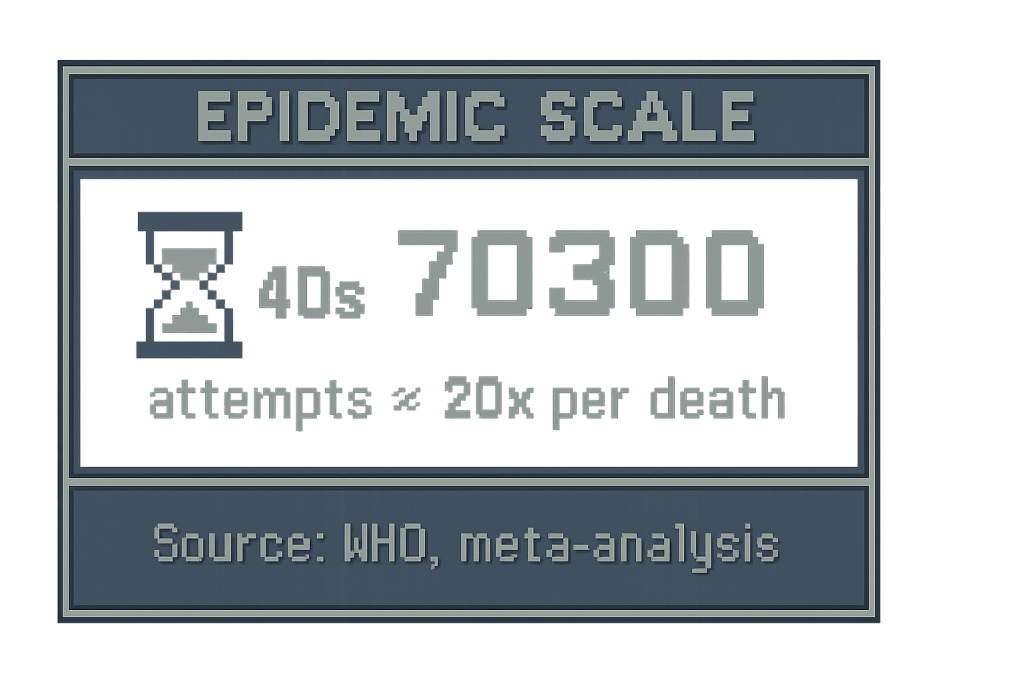

The proliferation of suicides in our time prompts us to examine this issue from a systemic perspective. The World Health Organization reports that 727,000 people died by suicide in 20211, a figure that excludes attempts. According to Director-General Ghebreyesus’s approximation2, this equates to one person dying by suicide every 40 seconds3. In the African Region4, suicides have exceeded the global daily average with a rate of 11 per 100,000 people. Moreover, attempts are multiplying in neoplastic proportions, finding their only parallel in Lovecraftian horror. For every suicide, it is estimated that there are about 20 non-fatal suicide attempts among the population5. Furthermore, in 2019, as specified by the WHO, 970 million people worldwide had a mental disorder, with depression and anxiety remaining the most recurrent, increasing by 28% and 26% respectively after COVID-19. These figures capture the situation in all its monstrosity, for the natural appearance of individual renunciation hides a kind of epidemic that silently disturbs life, increasingly bowing before death. An epidemic of insignificance, indefiniteness, “hedonic depression,” perpetual anxiety whose apex would only be this infamous and hollow path: suicide. Lovecraft succeeded in deciphering this subterranean apocalypse where we sink: “Now, as the baying of that dead, fleshless monstrosity grows louder and louder, and the stealthy whirring and flapping of those accursed web-wings circles closer and closer, I shall seek with my revolver the oblivion which is my only refuge from the unnamed and unnamable.“

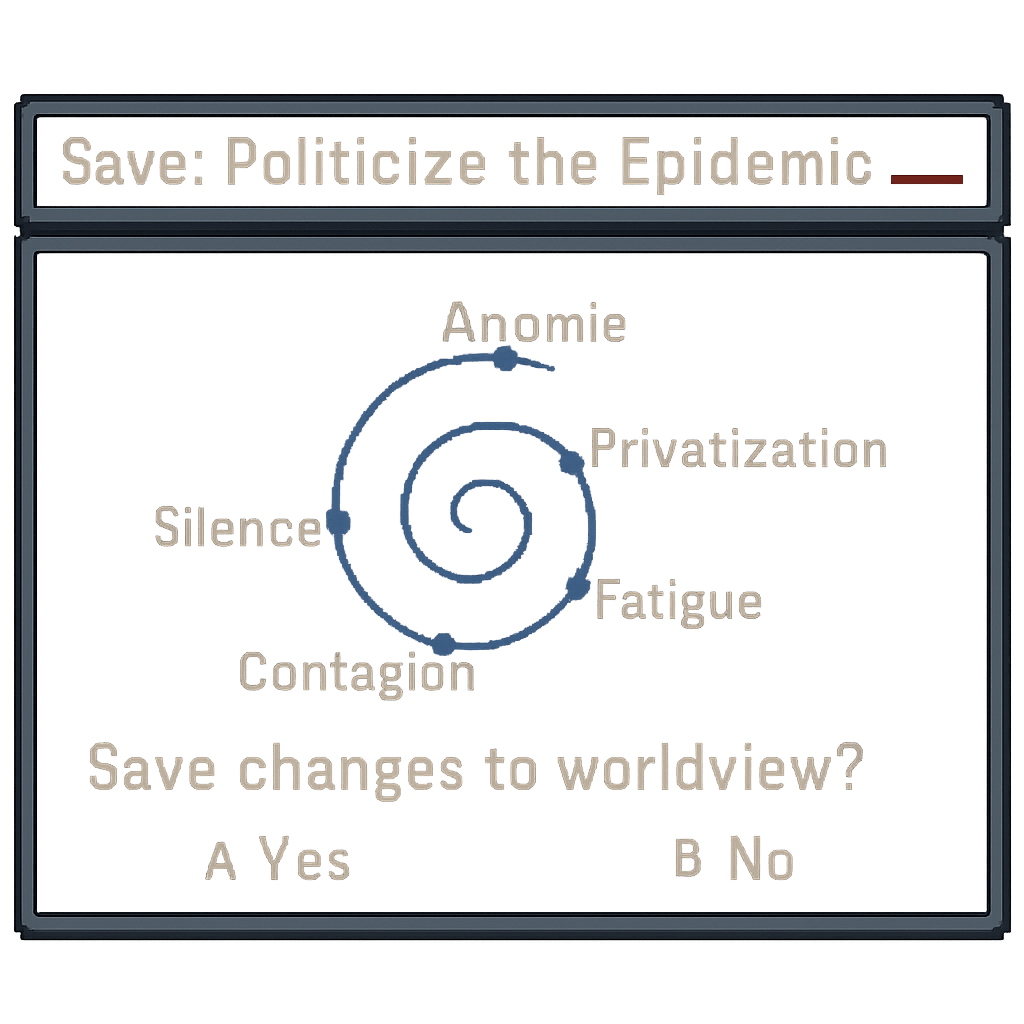

Durkheim was one of the first to detect this “holistic” dimension of suicide. By touching upon its eminently social nature, he invites us to look beyond the individual to understand “the producing cause of the phenomenon.” He establishes a typology of suicides: egoistic suicide, altruistic suicide, and anomic suicide. The latter is peculiar to the advanced industrial society. Unlike the stoic forms of suicide, Durkheim specifies that anomic suicide arises from the fact that “the activity [of individuals] is disordered and they suffer from it.” He argues that in industrial societies, individuals consume themselves in a state of deregulation (anomie) that results in a permanent dissatisfaction of appetites. “Appetites, no longer contained by a disoriented opinion,” he wrote, “no longer know where the bounds are before which they must stop.” Hence the need, according to the author, to discipline these appetites.

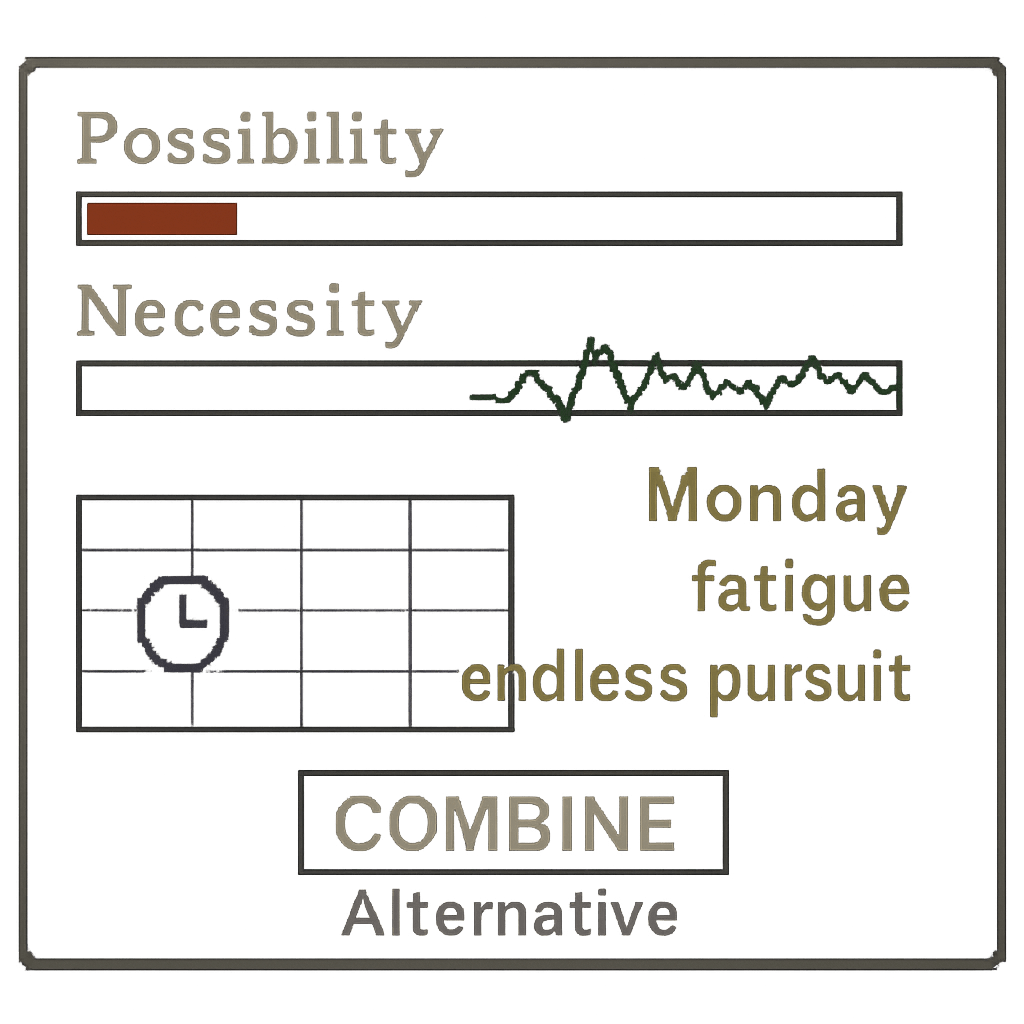

From my angle, I maintain that the anomie characterizing advanced industrial societies does not primarily stem from a lack of discipline of appetites but rather from the “despair of the possible.” Certainly, the moral need to discipline appetites matters in an intrinsically dysfunctional system and normalization of acute crises; nevertheless, paraphrasing Kierkegaard, the individual “despairs as much from a lack of possibility as from a lack of necessity.” The absence of possibility, the inability to visualize a way of life other than capitalism, is manifestly anomic. The “Sunday blues,” “miserable Monday mornings,” “Friday syndrome,” the imperishable fatigue are indicators (and the list is only indicative) of this state of deregulation rooted in advanced or post-industrial societies. Durkheim already noted that “fatigue alone suffices to produce disenchantment, for it is difficult not to feel, in the long run, the futility of an endless pursuit.“

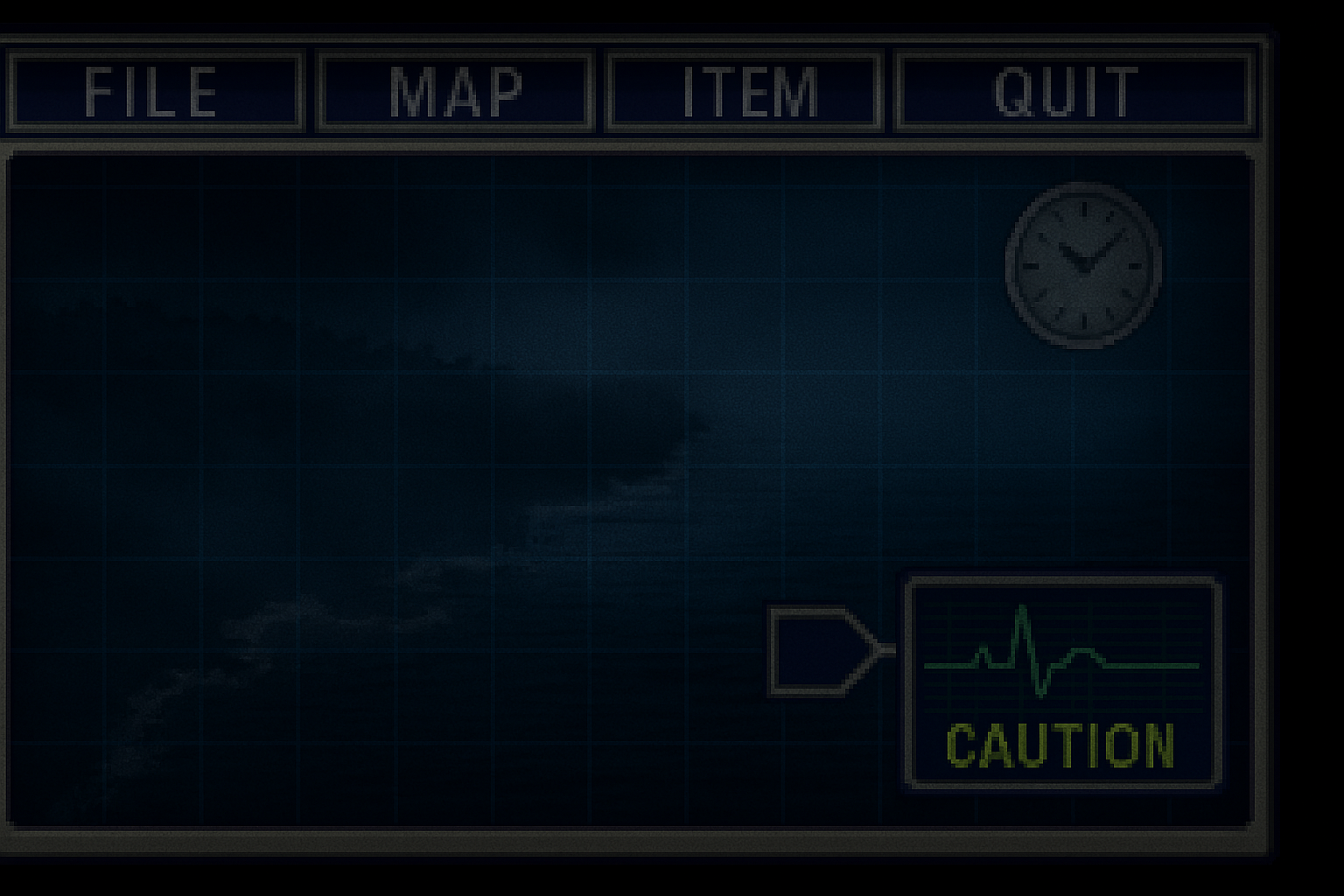

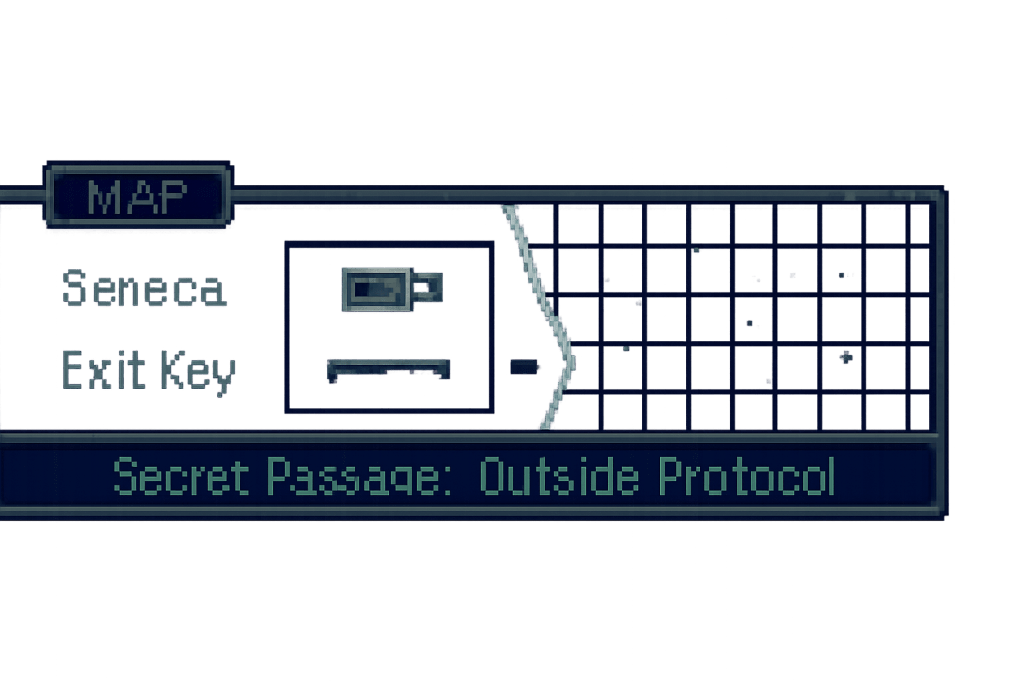

This great confinement in a single way of life, framed by cubicles that outline the existential space of post-Fordist precarity, stifles the self, resulting in cyber-specter employees who desperately carry their carcasses up the modular caves of movable cubicles. The political sphere, charged with adjusting this situation, only consolidates it, as those with political power, meaning “the monopoly of sovereign decision,” manipulate it for the benefit of Capital. This explains the concealment of this public health problem and its reduction to individual factors. Thus, epidemic suicide emerges as a political category whose specter stealthily haunts our societies.

The unspoken politics of self-annihilation

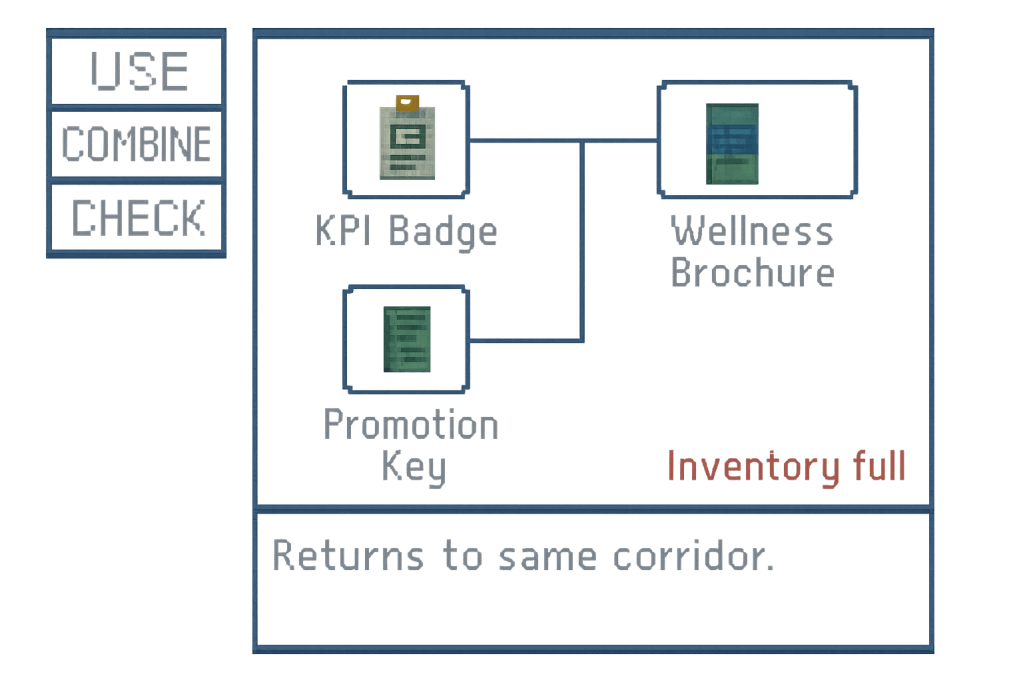

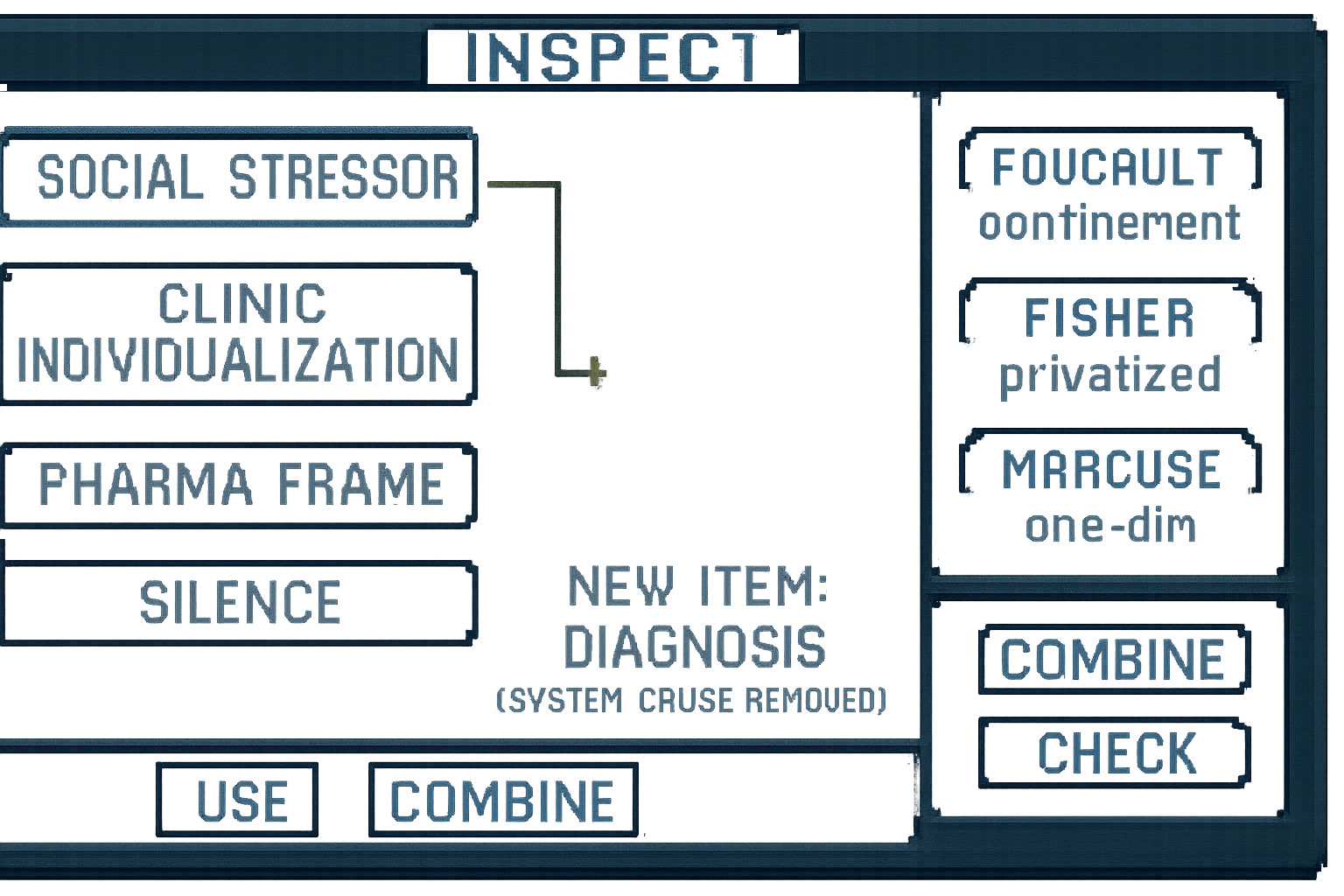

To grasp this last observation, it is essential to approach suicides within the encompassing framework of mental illnesses in the capitalist state. Michel Foucault observed that modern political rationality succeeded in confining madness within the individual sphere. “The problem of madness,” he said, “is no longer considered from the perspective of reason or order, but from the perspective of the individual’s right to freedom.” According to Foucault, the threshold of biological modernity for society is marked by life itself – the individual bodily life – becoming the primary stake of power. This biopower is indispensable to capitalism, a system which ‘’could only be secured through the controlled insertion of bodies into the apparatus of production and by an adjustment of population phenomena to economic processes.’’ It is this anatomo-political disciplinary practice that unveils the landscape of anomic dysfunctions.

Consequently, this individualization of mental illnesses quietly hides their systemic social causes. Mark Fisher noted in this sense that “by privatizing these problems – treating them as if they were caused only by chemical imbalances in the individual’s neurology and/or by their family background – any question of social systemic causation is ruled out.” In this regard, Fisher considers mental health issues as an aporia of what he called Capitalist Realism. Fisher argues that this system is inherently dysfunctional as it expresses a position diametrically opposed to the sustainability it claims to support. The transition into a precarious existence, the instability of employment, and the experience of being lost within dehumanizing schedules, ultimately, the obsolescence of humankind before the reign of privatized social life, these are all mediating forces that operate beyond the individual level. They can only be understood by delving into the systemic, down to the very core of the system. For Fisher, the politicization of mental health issues reveals this manifest systemic dysfunction in the correlation between neoliberalism and the proliferation of mental illnesses: “The mental health plague in capitalist societies would suggest that, instead of being the only social system that works, capitalism is inherently dysfunctional, and that the cost of it appearing to work is very high.”

In this way, we can only affirm that this generalized ideological atmosphere, promoted by a hegemonic discourse emanating from a “business ontology,” relegates the issue of suicide to the individual level by trivializing it. A trivialization that, in our view, reflects the cruelty of this planetary ideology. Herbert Marcuse, in defining his One-Dimensional Man, captured the terrifying nature of this discourse that always manages to mask its cruelty: “What is relatively new,” said Marcuse, “is that these lies are generally accepted by public and private opinion and that the monstrous nature of their content has ceased to appear. […] The syntax of reduction reconciles opposites by inserting them together into a solid and familiar structure.”

The sinister thus reduces to the internalized hell of the self, confined within the distorted image of madness. In this way, the hegemonic discourse pleads its innocence, leaving individuals at the unconscious gatekeeper of death without acknowledging the weight of the system; they abdicate to despair and choose to self-annihilate as good automatons in the face of the imposed image and its insurmountable framework. “It is the logic of a society that can do without logic and plays with destruction,” observed Herbert Marcuse, “a society that technologically controls mind and matter.“

‘’Something Possible, Otherwise, I Will Suffocate’’

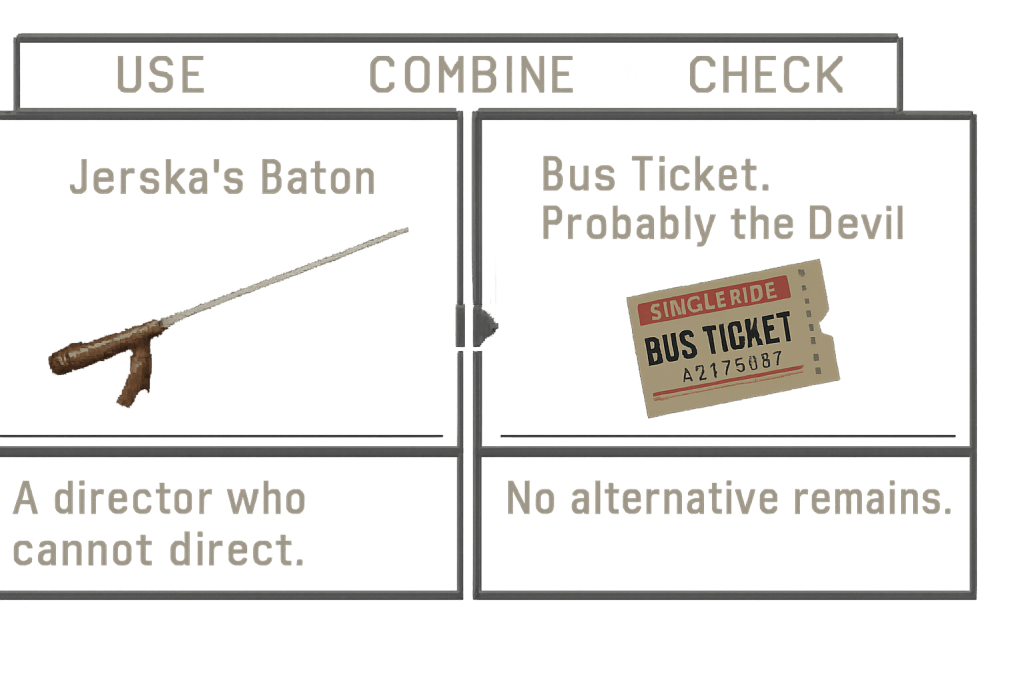

Post-Fordist society exacerbates the suicide epidemic, deepening its devastating consequences. Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s The Lives of Others captures the silent horror of this phenomenon with chilling precision. The film’s catalytic moment arrives with the suicide of Albert Jerska (Volkmar Kleinert), a director banned from practicing his art. His choice to end his life stems not from a lack of physical freedom – he moves unconstrained – but from the annihilation of possibility itself. Faced with a world that had erased his future, he saw no hope except in another life:

“In my next life, I’ll simply be an author. A happy author who can write whenever he wants. […] What is a director if he can’t direct? He’s a projectionist without a film, a miller without corn … He is nothing … Nothing at all …”

Jerska’s desperate gaze represents, in our view, the anomic renunciation of life that quadruples in our societies.

Similarly, Bresson’s suicidal character in “Le Diable, Probablement” represents the archetype of the individual who, in his indignation at this system, has realized the total absence of an alternative. Kierkegaard would say of Charles that he had an awareness of his “self” in killing himself: “the more one is lucid about oneself (self-awareness) in killing oneself, the more intense the despair one has.” An awareness of his reflective impotence in the face of this systemic madness.

The renunciation of life thus appears as a revolt against the systemic stagnation of a world that transforms by refusing to hear the groans of the desperate. The only viable escape from the system manifests itself as an umbilicus of Limbo– an elusive, subversive force that fractures the ordered structures of capitalist society. It disintegrates normativity’s rigid framework into the realm of possibility.

The descent

“Everything is insane in the system,” note Deleuze and Guattari. A monstrous system where humans devour themselves in their own obsolescence, it is by definition cruel and sinister since it makes Life a “pure impotence and distress.” Durkheim spoke of a “rise above particular suicides” to grasp its anomic character in advanced industrial societies; we prefer to speak of a Dantesque descent into the “hard and savage path” of the sinister, where the possible is abandoned. Perceiving the unity of suicide – its epidemic nature – involves politicizing it and exposing the symbolism of its violence.

To ignore is to condemn oneself to the post-apocalyptic silence of limbo. Paraphrasing Bataille’s cruel observation, the suicide becomes “a danger to those who remain: if they must bury him, it is less to put him away, than to put themselves away from this contagion.”

Further References:

Bataille, Georges, Œuvres Complètes, Vol. VIII, Editions Gallimard, Paris, 1976.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari, Capitalisme et Schizophrénie. L’Anti-Œdipe, Les Editions de Minuit, Paris, 1973.

Durkheim, Emile, Le Suicide. Etude de Sociologie, Félix Alcan, Editeur, Paris, 1897.

Fisher, Mark, Capitalist Realism. Is There No Alternative?, 0 Books, Winchester, 2009.

Foucault, Michel, Histoire de la folie à l’âge classique, Editions Gallimard, 1972.

Foucault, Michel, Histoire de la sexualité 1. La Volonté de Savoir, Éditions Gallimard, 1976.

Kierkegaard, Søren, Traité du Désespoir, Editions Gallimard, Paris, 2006.

Marcuse, Herbert, L’Homme Unidimensionnel. Essai sur l’idéologie de la société industrielle avancée, Les Editions de Minuit, Paris, 1968.

Seneca, Of Providence, URL: https://archive.org/details/seneca-of-providence

- World Health Organization, Suicide worldwide in 2021. Global health estimates, URL: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/381495/9789240110069-eng.pdf?sequence=1 ↩︎

- Ghebreyesus emphisizes that ‘’despite progress, one person still dies every 40 seconds from suicide. Every death is a tragedy for the family, friends and colleagues. Yet suicides are preventable. We call on all countries to incorporate proven suicide prevention strategies into national health and education programmes in a sustainable way.’’ URL: https://www.who.int/news/item/09-09-2019-suicide-one-person-dies-every-40-seconds ↩︎

- Consequently, the 2021 data shows an average of one death by suicide every 43.5 seconds. ↩︎

- The term “African Region” refers to a specific epidemiological classification used by the WHO. Unfortunately, the continent itself is often sidelined in broader discourse. A persistent colonial tendency to reduce Africa’s vast heterogeneity and significant demographic weight – it is the world’s second-largest and second most populous continent – to the myth of a single entity continues to affect how institutions approach phenomena within it. This is critically evident in suicide prevention, where rates vary significantly across nations and over time, revealing a fundamental lack of understanding of the issue across the continent’s diverse contexts. According to Becky Mars et al., ‘’little is actually known about the incidence and patterns of suicide across the continent. The information is of fundamental importance, both to help inform local, regional and national policy, and to provide a more accurate estimate of the magnitude of suicide globally.’’ Becky Mars, Stephanie Burrows, Heidi Hjelmeland, and David Gunnel, Suicidal behaviour across the African continent: a review of the literature, p.1-2, Mars et al. BMC Public Health 2014, URL: https://d-nb.info/1111415072/34 ↩︎

- Fateme Babajani, Nader Salari, Amin Hosseinian-Far, and al., Prevalence of suicide attempts across the African continent : A systematic review and meta-analysis, Asian Journal of Psychiatry, Vol°91, January 2024, URL : https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1876201823004355 ↩︎